Original post 8.8.2015 by Dr. Nettrice Gaskins via Musings of a Renagade Futurist

As part of the upcoming The PASEO art festival, I visited Taos, NM and worked with local youth on an interactive art installation. My arrival kicked off the STEMarts Lab @ The PASEO programming, a series of youth workshops based at schools across the district. This week’s activities culminated with a free outdoor projection piece on the Luna Chapel on the Couse-Sharp Historic Site (see above). I was inspired by the Native American artifacts that were used in paintings during the late 1850s. For example, the authentic painted ceramic tiles embedded in the Couse Studio fireplace reminded me of ancient Mimbres pottery, which was the main subject of a ISEA2012 Albuquerque workshop I co-facilitated.

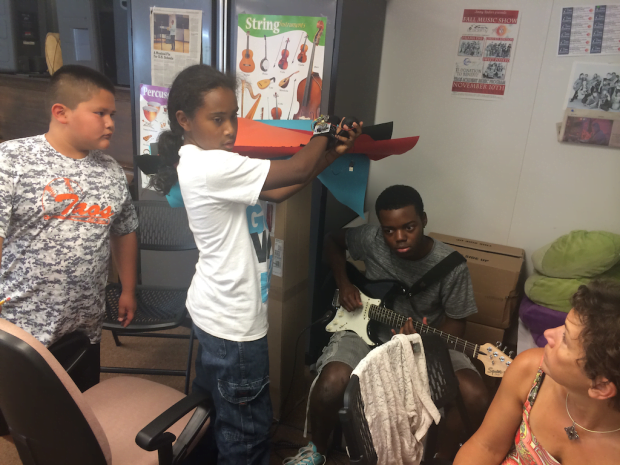

Elder Marie A. Reyna, Executive Director of the Oo-Oonah Art and Education Center helped recruit youth from the Taos Pueblo to attend the workshop. As a result of her, Karin Moulton’s and Agnes Chavez’s efforts, an ethnically diverse group of participants showed up to learn about the Electrofunk Mixtape: An AR Virtual Sounding Space. The goal of the workshop was to teach physical computing and video projection mapping to Taos youth, as well as to engage ethnically diverse students through culturally responsive teaching.

The STEMArts Workshop at Taos Academy

During the 1970s and 80s, a genre emerged that evolved the programming of electronic devices to make funk-y sounds. This genre was/is called electrofunk. The workshop took the electronic programming aspect of the genre and combined it with the mixtape, which is a compilation of songs recorded onto any audio format. To this I added the exploration of culturally (and environmentally) relevant outdoor art installations (i.e., Bert Benally and Ai Weiwei).

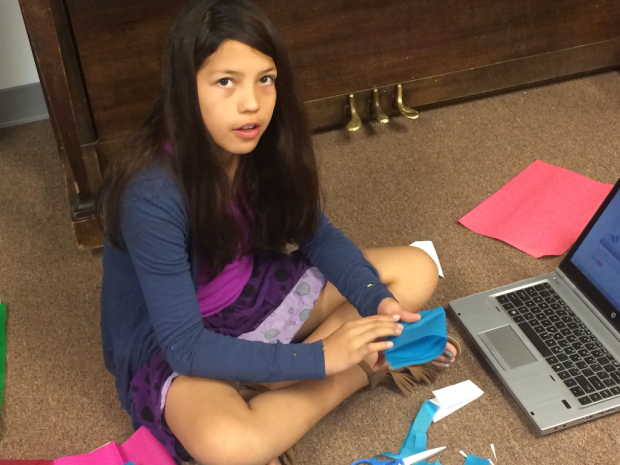

The idea of mixing different sounds and images using electronics was introduced to the participants and they spent the first day brainstorming and trying out different materials and methods. The goal was for them to learn and practice new skills, learn how to communicate and work together in teams. In other words: forming, storming, norming and performing.

The participants were really interested in using the sound glove, so I wanted them to explore how they might use one in an interactive art installation. The glove converts colors to musical notes. One group used it to identify the notes for a color-based project that could be played by the glove wearer. They spent time “playing” colors with the glove and composing music using real instruments to play the same notes.

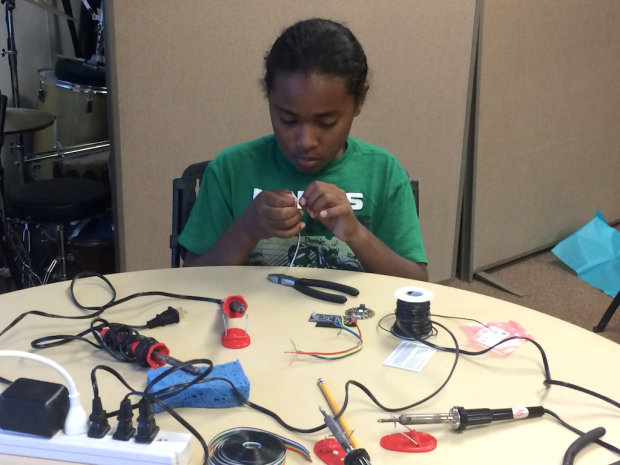

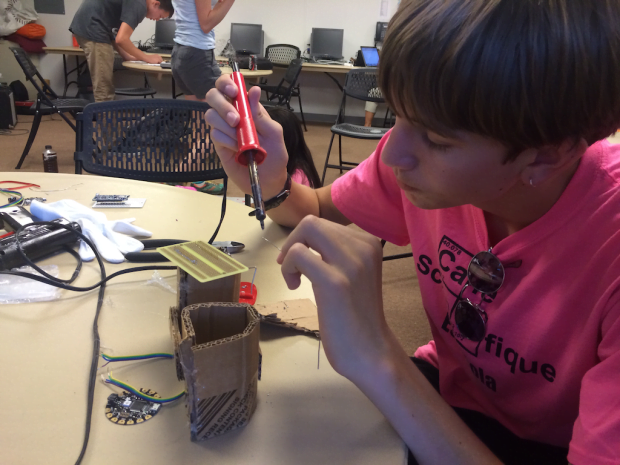

The second day was more focused and participants worked on projects for The Paseo art installation such as soldering electronic components for the sound glove, creating sculptures using wire and colored tissue paper that will light up in the dark, and using Figure to compose songs. Figure is an iOS mobile application that allows users to create songs using different patterns from electronic devices such as the Roland TR-808, which was used in electrofunk music.

At the site for the final installation there is a “rock house” and a short rock wall that gave me the idea of creating electroluminescent “rocks” that respond to sounds. The youth took this idea and ran with it, using chicken wire and colored tissue paper. Later, I will create electronics (and even more electronics) to make the colored objects light up and interact with sounds.

On the third day we wrapped up the projects and I taught the participants how to use Magic Music Visuals to generate different image patterns that respond to sounds. Each participant was asked to select an image to use for the Pre-Paseo event at the Couse-Sharp site. I was impressed by the group’s hard work even though I knew they would rather play (or take longer breaks).

The Pre-PASEO Pop-Up Event

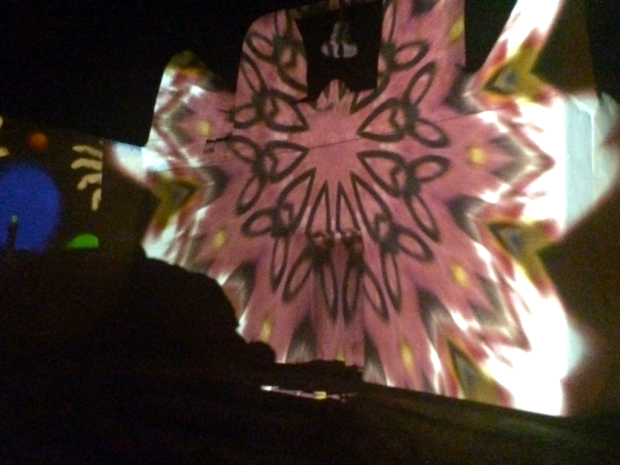

Later that day, the Taos community showed up for the ‘pop-up’ and I set up the laptop to project images (music visuals) on the outside walls of the Couse-Sharp Luna chapel. I used art/images created by the youth during the workshop and a feature in Magic Music Visuals that generates abstract visual patterns using live video.

The music was provided by local DJ Oliver and the event was covered by local news. The youth showed up with their families and some of the workshop participants helped test the software. Then, something really interesting happened. After introductions were made, native youth demonstrated what they had learned in the workshop. I stepped back and let them take over the VJing duties. I encouraged the audience to join in and the youth facilitated their participation.

Taos Pueblo elder Marie A. Reyna also participated and she spoke. This was one of the highlights of the event.

Reflections

Of course there were challenges but, overall, the youth workshop and kick-off event was successful. During the workshop, I saw the five essential elements of culturally responsive teaching: developing a knowledge base about cultural diversity, including ethnic and cultural diversity content in the curriculum; demonstrating caring and building learning communities; communicating with ethnically diverse students; and responding to ethnic diversity in the delivery of instruction.

It touched my heart to see elders and families from the Taos Pueblos show up (early) for the culminating event. In many ways, the exposure to culture, technology and art transformed the youth. The Taos community could see the learning demonstrated when the participants VJed the pop-up event.

One of the youngest participants went from literally hiding under a table to leading the VJ activity during the pop-up event. When her images were projected on the Luna chapel wall I encouraged her to tell her grandmother who I had met at the Pueblo. Another youth was very interested in the live video capture feature of Magic Music Visuals. Towards the end of the event, she experimented with software as DJ Oliver wrapped up his set.

In many ways, this workshop demonstrated techno-vernacular creativity and culturally responsive teaching, which is based on the assumption that when (STEAM) knowledge and skills are situated within the lived experiences and frames of reference of students, they are more personally meaningful, have higher interest appeal, and are learned more easily and thoroughly (Gay, 2000). As a result, the academic achievement of ethnically diverse students will improve when they are taught through their own cultural and experiential filters (Au & Kawakami, 1994; Foster, 1995; Gay, 2000; Hollins, 1996; Kleinfeld, 1975; Ladson-Billings, 1994, 1995).

References

Au, K. H., & Kawakami, A. J. (1994). Cultural congruence in instruction. In E. R. Hollins, J. E. King, & W. C. Hayman (Eds.), Teaching diverse populations: Formulating a knowledge base (pp. 5-23). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Foster, M. (1995). African American teachers and culturally relevant pedagogy. In J. A. Banks & C.A.M. Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (pp. 570-581). New York: Macmillan.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hollins, E. R. (1996). Culture in school learning: Revealing the deep meaning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kleinfeld, J. (1975). Effective teachers of Eskimo and Indian students. School Review, 83(2), 301-344.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African-American children. San Francisco: JosseyBass.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491.